- Home

- Niagara Falls Hotels

- Restaurants

- Casinos

- Niagara Falls Shut Off

- Niagara Falls USA

- Aquarium of Niagara Falls

- Goat Island

- Lewiston

- Lockport Caves

- Niagara Falls Cave of the Winds

- Niagara Falls Culinary Institute

- Fashion Outlets of Niagara Falls

- Niagara Falls Observation Tower

- Niagara Falls State Park

- Niagara Fishery

- Niagara Gorge Discovery Center

- Niagara Power Vista

- Maid of the Mist

- Oakwood Cemetery

- Old Fort Niagara

- Rainbow Bridge

- Niagara Falls Canada

- Daredevils

- Links

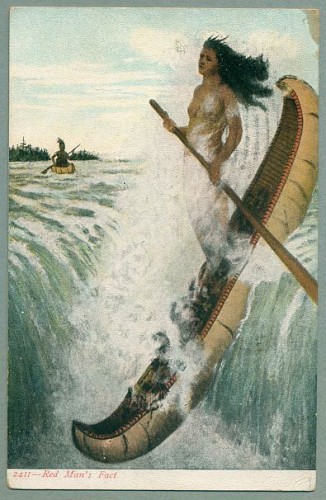

Niagara Falls Mythology “Maid of The Mist”

Niagara Falls Mythology

Niagara Falls mythology is fascinating, especially considering that Niagara Falls is so rich in native American lore, stories and legend. None more famous than the legend of the Maid of the Mist. This is how the stories ago according author Sue Wilson.

There are several different published versions of the “Maid of the Mist” legend. Some of these have become quite controversial among the Huadenosaunee as a whole, and in particular among the Senecas with whom the legend is associated, because of the misappropriation and distortion of culturally important themes to the Haudenosaunee.

The controversy focuses on the role and intent of the maiden herself. Almost all versions have her going over the waterfall at Niagara, NY. This is where the similarities end.

The original Haudenosaunee myth indicates the Maid having done so by her own free will in a suicide attempt. The Non-Native revisionist’s versions however, demonize Native culture by inventing a narrative that has the maiden being the victim of an annual human sacrifice ritual which is part of traditional Iroquois custom. Unfortunately, the melodramatic “beautiful Indian maiden sacrificed against her will in annual appease the gods now or pay in spades later” was swiftly adopted by popular culture. The pop culture version has been marketed with such skill that many people, including some Haudenosaunee, have been duped into accepting the veracity of such euro-centric myths.

This questionable behavior attributes to the Haudenosaunee culture triggered many scholars to search for the truth. After much research, both Native and non-Native scholars conclude there has never been any proof that Haudenosaunee people were ever involved in human sacrifice. On the contrary, the Haudenasaunee held their women in the highest regard. Unlike the intrusive European cultures of the time, their women held critical roles and responsibilities within the government and communities. The Haudenosaunee’s respect for the sanctity of women’s role in the creation of life, not the waste of it, motivated them be one of the first peoples to have equal suffrage.

This questionable behavior attributes to the Haudenosaunee culture triggered many scholars to search for the truth. After much research, both Native and non-Native scholars conclude there has never been any proof that Haudenosaunee people were ever involved in human sacrifice. On the contrary, the Haudenasaunee held their women in the highest regard. Unlike the intrusive European cultures of the time, their women held critical roles and responsibilities within the government and communities. The Haudenosaunee’s respect for the sanctity of women’s role in the creation of life, not the waste of it, motivated them be one of the first peoples to have equal suffrage.

Erroneous versions of the myth have been printed from as far back as the seventeenth century to the present. Donald E. Loker, Niagara Falls Public Library historian for the area found one influential source for such versions. He directs partial blame to Robert Cavelier de La Salle, a European explorer that had contact with the Iroquois in 1679. The visitor traded his knowledge of guns, ammunition and the subsequent advantages of using guns with their enemies, for information on agriculture, hunting and gathering techniques.

In Cavelier de La Salle’s writings about his visit with the Haudenosaunee, particularly the supposed sacrifice, the explorer exclaimed, “When learning of this yearly sacrifice, I attempted to stop them of such a practice.” He also recorded that he witnessed a horrible sacrifice first-hand when the chosen virgin maiden of that year was a “Chief Eagle Eye’s daughter named Lelawala.” He explains that the Chief changed his mind about sacrificing his own daughter, darted out after her in his own canoe and both fell to their death. The author concluded that the “Iroquois believed that after their deaths, both were changed into pure spirits of strength and goodness. The Chief would be the ruler of the cataract and she would be the Maid of the Mist. “

Cavelier de La Salle’s wife would later deny these accounts among the Haudenosaunee. She admitted that her husband had wanted to present the Iroquois as an ignorant people from whom it would be easy to take their land and colonize it. If they were sufficiently demonized no one would have sympathy for them and oppose the idea either. These revelations would also receive great praise from the King and Queen of France and most importantly, financial backing for future expeditions. The explorer’s compatriots, adventurers without pay, would also accept these ideas because they were hoping for land claims as a reward for their service.

She further stated that the Haudenosaunee people did not deserve de La Salle’s false representations, having showed extreme intelligence and hospitality.

Fiction became fact in 1846, when the “Maid of the Mist” Corporation in Niagara, New York, used the story to inaugurate their new boat ride at the Falls. The story stuck and was retold to thousands of tourists from all over the world.

The Haudenosaunee people, however, didn’t accept the arrogance of the non-Native people and denounced the false versions. Threatening protest, the Native people began promoting the truthful version which had been passed down through oral tradition.

The legend is considered a sacred lesson and must be retold to the people. Correct versions have been told to the people by such distinguished Haudenosaunee Chiefs and spokespeople as J.N.B. Hewitt, J.J. Corn Planter, Handsome Lake, Ely S. Parker, Arthur C. Parker, David Cusick, Elias Johnson, John Mt. Pleasant and Clinton Rickard. These men told the story as it had been handed down to them by their elders. A piece written in 1914 by the Buffalo Historical Society supported the Haudenosaunee’s doubts and the debate grew larger. As a result, several versions were corrected or placed out of print. “Legends of New York,” published in 1925, originally thought to be reliable, was put out of print. Over all the academic community has been more forthcoming than commercial enterprises at the Falls in supporting the genuine, sacred versions. Recently, Seneca Nation members, together with other Haudenosaunee and non-Native supporters threatened to protest the Maid of the Mist Corp. if they didn’t discontinue promoting the incorrect version to their customers. James Glynn, president, finally agreed to stop reciting the distorted version to boat riders. This was a substantive concession to the Haudenosaunee.

Since then there have been new publications written to promote the genuine version. Native cultures are living cultures, our stories reside in our people and our people reside in their stories. Individual storytellers exhibit flexibility and pragmatism in their delivery, but the central theme and its purpose are sacrosanct. The Maid is never sacrificed. She attempts suicide and is rescued by the Thuderbeings where she lives and learns from them the proper teachings of the Creator. The Maid is redeemed when she returns to her people and shares the Creator’s instructions with them. This is where our Haudenosaunee legend begins.